The BBC reported the death of John Jenkins as

Welsh bomber who attacked Prince Charles’ investiture dies at 87 [i]

He was described as “mastermind of a Welsh nationalist bombing campaign which targeted Prince Charles’s investiture has died aged 87.

The death of the former social worker and sergeant with the Army’s Dental Corp came peacefully in his sleep at Wrexham Maelor Hospital,on 17 December 2020’ . John Jenkins was also remembered as the former leader of Welsh paramilitary group Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru (MAC). This grew out of the anger and frustration at the drowning of the Cwm Celyn valley and the Capel Celyn village to make a reservoir for Liverpool in 1963. He was one of the most significant figures in the Welsh militant national struggle of the twentieth century. Late in life given some recognition as a man of “fierce principle who suffered much for a cause he believed in, and for a country he loved dearly” in a biography by Dr Wyn Thomas [see previous post ].

John Jenkins organised explosions to disrupt the Prince of Wales’ ceremony in Caernarfon Castle in July 1969. A device exploded unexpectedly, killing two members of the MAC in Abergele, Alwyn Jones and George Taylor. Many believe the actual target was the railway line at Abergele, a claim that has always been denied by the leadership of MAC. In fact, at the time the bomb was being placed, the Royal Train had already passed Abergele and was parked at a guarded remote site.

The following day two other bombs were planted in Caernarfon, one in the local police constable’s garden which exploded as the 21-gun salute was fired.

Another was planted in an iron forge near the castle but failed to go off. This bomb later exploded when a 10-year-old boy Ian Cox who was on holiday from England stood on the bomb when they retrieved a ball. He was badly injured in the blast lost his right leg and suffered bad burns.

The final bomb was placed on Llandudno Pier and was designed to stop the Royal Yacht Britannia from docking. This device also failed to explode.

The BBC report focused on the1969 Investure recalling that Jenkins, who had led MAC whilst still a non-commissioned Army officer, said he had been put under pressure to try and assassinate Prince Charles

“One of the hardest fights I ever had was with our own people,” he said.

“I spent a lot of time in the weeks before the investiture travelling around in an army civilian car, reining people in.

“They were becoming more, well, savage as the ceremony approached.”

He said he stressed his view that an assassination would achieve “nothing” politically, though be believed it would have been “possible”.

From 1963 to 1969 MAC set off bombs and devices to damage water pipes and government buildings throughout Wales, including the South Stack Relay Station which was an important communication hub between the UK Ministry of Defence and its troops in N. Ireland. The campaign was undertaken in the belief that the political voice of Wales was being ignored.

Bernard Moffatt, Assistant General Secretary Celtic League, recalled,

“Finally Jenkins was arrested more by accident and design and then had to endure some of his former colleagues who had worked with him in MAC giving evidence against him. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison of which he served six. During his time in prison he went on hunger strike several times. His prison conditions were also a source of a reference to the European Court of Human Rights when he was denied access to the Breton language newspaper ‘Le Peuple Breton’.

Later he was also arrested briefly during the Meibion Glyndŵr campaign but there is no evidence he was involved in this. He was also arrested and served about eighteen months imprisonment in the 1980s in connection with another series of bombings. Jenkins only role in this appeared to be assisting another person over bail a fine had been expected but the State wanting its pound of flesh imposed the custodial sentence.” [ii]

The Welsh Daily Post noted John Jenkins, who orchestrated the 1960s bombing campaign in Wales, was revered as a hero among some independence campaigners, and head its report:

Prince Charles’ Investiture bomb campaign plotter remembered as ‘one of Wales’ greatest patriots’ [iii]

Jenkins was more fondly honoured in Remembering A Welsh Patriot the account on the website, Gwlad a new voice for an independent Wales[iv]

“Gwlad Leader Gwyn Wigley Evans said the people of Wales needed to remember not only Jenkins’s personal sacrifice, but the fact that the nation was still not free.

‘As a party, we are obviously dedicated to a non-violent approach to tackling Wales’s problems today’ he said.

‘But, that’s not to say, we can’t remember John Jenkins’s lifelong dedication to Wales and the fact that we are still living with the situation that he drew our attention to in the 1960s.’

Mr Evans said John Jenkins exposed the way that the British establishment co-opted the ‘great and the good’ in Wales to foist an English prince on the people of Wales in 1969 to keep the Welsh in their place.

‘The sad truth is that the British establishment are still up to their dirty tricks and manipulation fifty years on’ he said.”

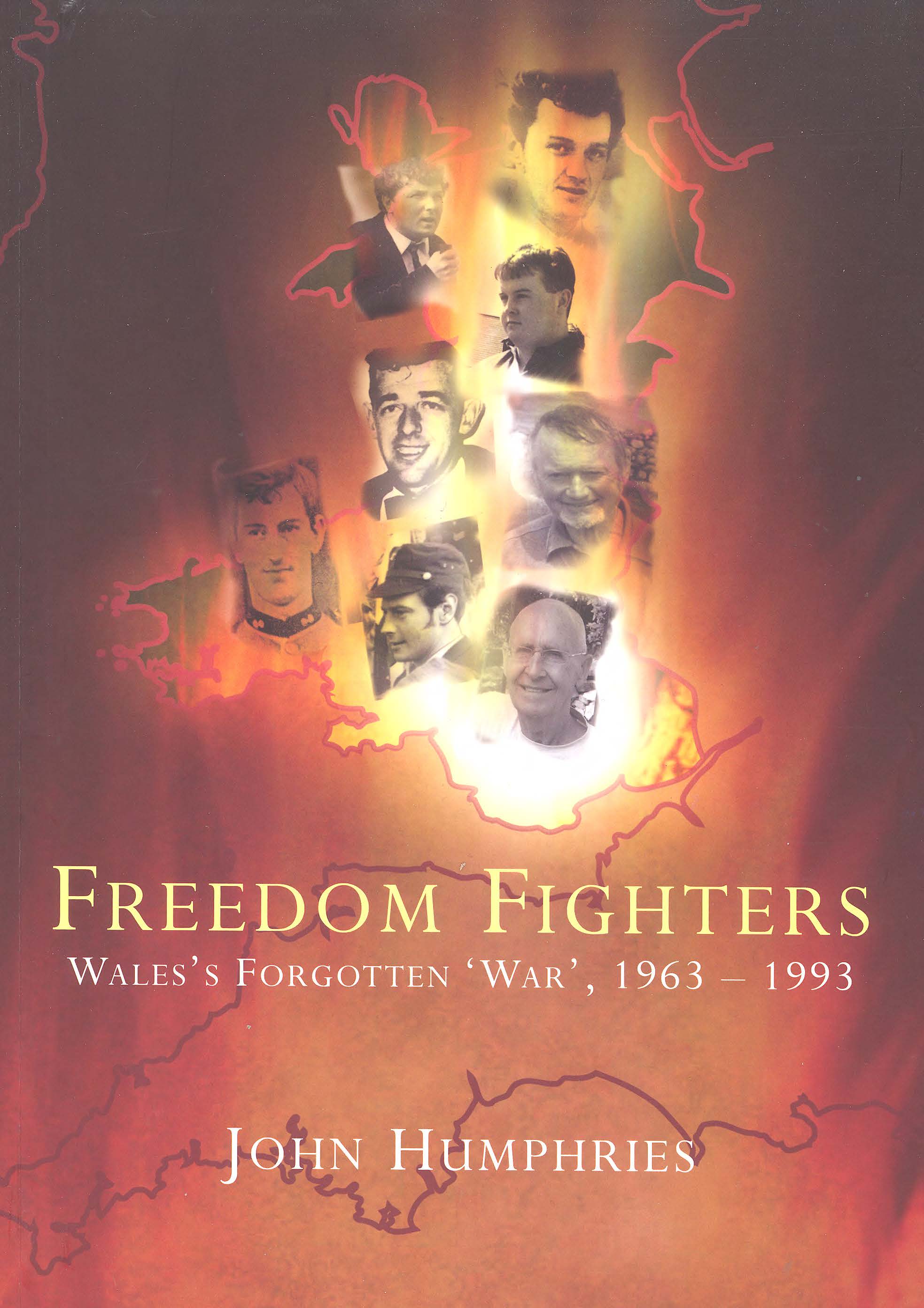

John Barnard Jenkins pictured in Flintshire in 2009

Tributes have been paid after the man died, aged 87.

“ Gwynedd councillor Owain Williams, one of the founders of MAC, who was himself jailed for bombing the Tryweryn dam in 1963, described Jenkins as one of Wales’ great heroes.

He said: “I can honestly say, hand on my heart,that he was the greatest patriot to have lived in the last century, there’s no question about that.

“John took the ultimate step by throwing the first stone.

“For that, he has been ostracised from his own country. John was an embarrassment to [the establishment]. His actions and his words meant they didn’t want anything to do with him.

“They didn’t realise that but for the actions of John and a handful of others in the MAC, they would not be masquerading in Cardiff Bay today in the Welsh Parliament.”

He added: “He was a very clever operator, there’s no question about that. He valued human life and he was very disturbed by the death of two of his comrades. He felt very bad about that. I know that upset him greatly.

“Every country has its heroes and its martyrs, but I can truly say that since the days of Owain Glyndŵr he was probably the stand out.

“I can only respect him.

“I think the most positive thing in Wales at the moment, it’s not our political parties, it’s the Yes Cymru campaign.

“John Jenkins made the foundation stone.

“I hope in his last days he could at least be proud of what he began and what he suffered for.

In a documentary by Huw Edwards, made for BBC Cymru, Jenkins speaks of the period and summaries it and his view : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pl7SQdsJ4So

REFERENCES

[i] 18 December 2020 https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-55361718

[ii] JOHN BARNARD JENKINS RIP (1933 – 2020) A WELSH HERO

[iii] https://www.dailypost.co.uk/news/north-wales-news/prince-charles-investiture-bomb-campaign-19485643

[iv] https://gwlad.org/en/english-remembering-a-welsh-patriot/

elyn, the last Welsh Prince of Wales , that was remembered and celebrated annually on December 11th, a memorial day was established on July 4th in memory of two MAC patriots killed in 1969. The great Merthyr Uprising of 1831 was commemorated on June 6th; the national hero of Wales, Owain Glyndwr honoured on the 16th September

elyn, the last Welsh Prince of Wales , that was remembered and celebrated annually on December 11th, a memorial day was established on July 4th in memory of two MAC patriots killed in 1969. The great Merthyr Uprising of 1831 was commemorated on June 6th; the national hero of Wales, Owain Glyndwr honoured on the 16th September produced results for Plaid Cymru by undermining English government intransigence”

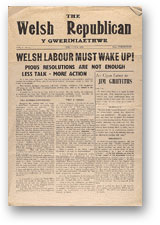

produced results for Plaid Cymru by undermining English government intransigence”  u members decided to walk out of the conference and set about creating their own party, publishing up to 1957 the English language periodical, The Welsh Republic. (Y Gweriniaethwr).

u members decided to walk out of the conference and set about creating their own party, publishing up to 1957 the English language periodical, The Welsh Republic. (Y Gweriniaethwr).